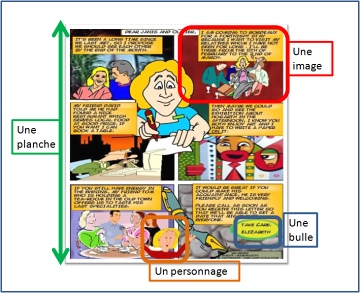

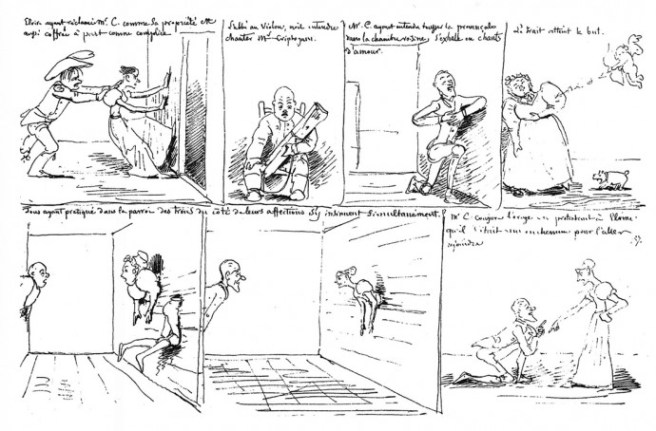

It took several years, but I finally picked up a few books from the Adventures of Tin Tin collection. I’ve been trying to branch out from my rather narrow focus on World War II related books, and I realized I have never read any Tin Tin which, alongside Asterix, are probably some of the best-known examples of bande dessines. Tin Tin is also classic example of the ligne claire style which features dark black outlines and bright colors.

I started off with the adventure in Tibet, the 20th book in the series. It came highly recommended and I think it was a great place to start. Herge, the artist, drew lavish backgrounds based on photographs from Tibet. Tin Tin’s Tibetan expedition includes a compelling story based on friendship and adventure. It’s also based in a single exotic locale that is explored in more detail, as opposed to the “Cigars of the Pharaoh”, which I’ll discuss next.

The “Cigars of the Pharaoh” is the 4th book in the Tin Tin series and I found it to be much less compelling than the Tibetan story. This adventure begins in Egypt but shifts abruptly to India. The story is rather far-fetched as Tin Tin combats an international drug cartel. Although Africans appear in the story only briefly, Herge presented them in a very racist caricature. The book was originally produced in 1934, and Herge later disavowed this attitude. However, I did enjoy the introduction of Thomson and Thompson (or Dupont and Dupond in the French version) – two nearly identical detectives. The duo are uncharacteristically effective as compared to their later bumbling, which is my next target.

The “Jewels of Castafiore” is a rather claustrophobic story compared to Tin Tin’s previously wide-ranging adventures. It’s set entirely at the country estate of Tin Tin’s companion Captain Haddock where a house guest reports her prize jewels have been stolen. However, the story grows rather tiresome after it’s discovered the jewels aren’t really missing and the whole farce is repeated several more times. Thomson and Thompson are depicted as comically ineffective this time around. Compared to the racism earlier in the collection, this book features Tin Tin and Captain Haddock standing up against the persecution of Romani people.

I feel like these books gave me a representative slice of the Tin Tin collection. I might pick up a few more, but I doubt I’ll complete the whole series. Each story gave me a few chuckles and were pretty fun for the most part. I really enjoyed “Tin Tin in Tibet” and the “Blue Lotus” was its prequel. Other critics have denounced some of Herge’s early works, such as overt racism in Tin Tin’s Congolese adventure, so I’ll probably skip those. In addition, Tin Tin is merely an observer in the earlier stories as opposed to a full participant in the later adventures that I read. I enjoyed seeing Tin Tin evolve through the series, but maybe I’ll even try some science-fiction next…